The Black Experience on Cape Cod

There is no one singular black American experience. The black experience varies everywhere you go. It’s in the south from Texas to Florida. It migrated into the Northern cities like Deitrot and Chicago. It’s been where buildings tower high and poets sing from the rooftops.

Though, I find myself thinking about the kinds of culture that aren’t as well documented. Even though I have lived my entire life here, I still find myself asking the question, what is like being black on Cape Cod? Since September I’ve been interviewing black people in Barnstable about their experiences living, working and growing up on Cape Cod. What follows is portions of the interviews I conducted with these people who spoke openly about racism and prejudice.

By highlighting experiences of those who live here, I hope to open your eyes to what it truly means to be black in a place such as Cape Cod.

“I worked 23 boots to the ground with marginalized communities, I worked with people like me who came from nothing,” Wallace said.

Tara Wallace is a mentor, community member, wife, and mother. She has spent the past 23 years of her life using her voice as a person of color on Cape Cod to help others. Her life began in the New York city burrow of the Bronx, when she said she “escaped from a bad situation.” She came to Cape Cod at just 17 years old, not knowing anyone but her grandma who passed away only three months after her arrival.

“I was in a shelter but going to Cape Cod Community College,” Wallace said.

To finish her administrative technology certificate program, she had to intern at a local nonprofit organization. She worked at the Housing Assistance Corporation. HAC has helped those in the Cape and Island area with getting affordable housing for 50 years.

“I learned so much and I went up in that organization and learned the power of my voice,” she said.

Wallace decided to create her own path of action in 2020. After the murder of George Floyd, Wallace said she felt so much anger and decided to do something with that anger. After watching countless groups say things but never take action, she decides to take things into her own hands.

He was not the first black man to be killed by police brutality and she was getting fed up. “You hear all the time about black people getting murdered and I was tired of people saying things but not doing anything. I wanted action,” said Wallace.

She decided to create her own group that would uplift not only the black community but help all people of color. “I decided to do something about my anger. I founded Amplify POC,” said Wallace.

Amplify POC is not just about fighting for people of color in the realm of police brutality but the inequality that black people face in many different realms of discrimination.

“Pay equity is a big thing for me. We do workshops that uplift businesses, we bring in artists. The events we do are a big deal because it helps to heal within the community together.” Wallace said.

Using her nonprofit, Wallace has hosted countless events that have brought together and uplifted businesses owned by people of color in her community. “The events are a big deal because it helps heal within the community and bring us together,” Wallace said.

Even though she works with people in her local community, she also fights at a higher level.

“We go to the legislative level. When we’re advocating about policy on a legislative level, it’s about everything that affects us,” said Wallace.

Amplify POC has created a purpose for Wallace, it has helped her to feel like she isn’t just doing nothing.

“I have to fight harder sometimes and I have to hold a higher level of standard,” said Wallace.

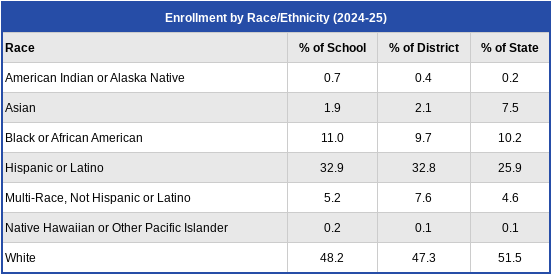

According to the Massachusetts Department of Elementary & Secondary Education, for the 2024-25 school year, only 11% of students enrolled at Barnstable High School are black or African American. In comparison, 48.2% of the population is made of white students and 32.9% are Hispanic or Latino.

Barnstable High School has no black counselors or black hub administrators. There are only a handful of black teachers that currently work inside of the school. How can black students feel seen or represented if they cannot speak to anyone who looks, acts or talks like them?

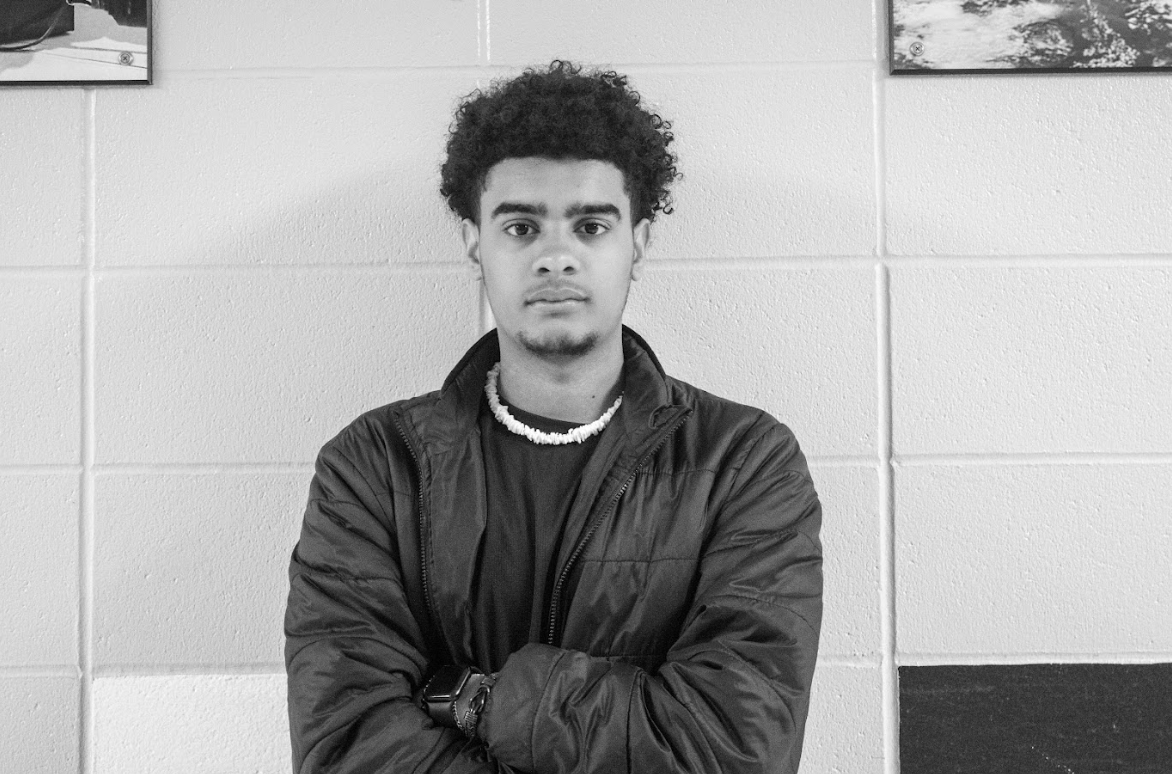

“People look at you differently from how they look at other people. Not always positively and not always negatively but differently. I have had to adapt to that my whole life,” said senior at Barnstable High School, Jaden Jeffries.

Jefferies, originally born in Detroit Michigan, has lived on Cape Cod since he was a few months old. He has been going back and forth between the two places his whole life. Growing up on Cape Cod and then going to see his family in Detroit, Jeffries has seen the stark comparison between cultures.

“The way people talk, act and look is different,” Jeffries said. “There is more African American culture there,”

Being black on Cape Cod has a different look than being black in predominantly black areas does. In Jeffries’ experience, he doesn’t have a place within any “group”.

“I’m very different because I’m considered whitewashed, so I’m too white to be with the black crew but to black to be with the white crew so I connect with everyone but I’m not super close to either group of people,” said Jeffries.

You often hear this word thrown at black people who grow up in predominantly white areas because of the way they talk, how they dress and the vernacular they use. The real question to ask is what is being whitewashed and what is not having your own culture because there isn’t any.

There is no particular way to act white, there is only acting in a way that is not what is expected of you. To be black and act white is to speak ‘properly’ or dress in a way that isn’t considered stereotypically black.

“If I grew up in Detroit I would have a similar personality but with a different look,” Jeffries said. “I would be similar but I would express myself differently,”

Self expression is not only based upon who you are as a person but the things you see, experience and how you feel. Many of the things that determine the way we express ourselves we see in the places where we spend most of our time. Whether it be home, work or school, we pick things up. But what if there is no one who looks like you in the place you spend a quarter of your life?

“My education hasn’t been affected but my standings,” Jeffries said. “Last year, as far as standing in our grade, I was top 10% and I had a 4.5 GPA, then into this year my fell off and I’m top 30% with a 4.1 GPA,”

“And obviously that’s still good but last year was phenomenal, I talked to my counselor and she still says it’s phenomenal, it’s above average, it’s great.”

“I feel like African Americans are looked at as less intelligent so my top 30% to other people is crazy above average when realistically it’s not too insane. If I was white and had the same standings, it would be good but it wouldn’t be nearly as impressive because of the color of my skin,” he said.

Like I said, there is no one black experience. There are so many different paths in the diaspora of black people that live on Cape Cod.

“Often latinos aren’t recognized as also being African or being black, so it’s really hard to come to terms with the fact you can be both,” said senior Paloma Savinon.

Savinon and her family are originally from the Dominican Republic, from which they moved when she was just four years old. She has been on Cape for the past 14 years of her life.

In her experience, a lot of people are negative about the idea of being both black and latino or being both black and hispanic.

“I’ve had multiple people here tell me here ‘oh no, you’re not actually black you’re just Dominican’,” she said.

Savinon has seen that there are aspects of black culture that don’t align with latin culture, which forces people to have to tow the line between both things.

“It’s hard to belong to one community when you are a part of so many other things,” said Savinon.

Even though people do not often recognize her identity, Savinon still faces racism in her life.

“I live by Wequaquet and there’s a private beach that we’re allowed to use but every time I’ve gone, someone has asked me where I live,” she said.

While at a recent Barnstable school committee meeting, it was announced that Savinon was accepted to and attending Boston College. When someone from the community came up to speak at the meeting, the person congratulated the white student sitting next to her, not Savinon.

“It’s mainly microaggressions; now in this day and age it’s hard for someone to be racist to your face,” Savinon said.

It’s important to not only highlight the marginalized voices but it’s vital to understand how and why these voices are marginalized. The next interview is of William Penni, speaking honestly about his experience with racism and prejudice as a white person in white spaces.

“A lot of white people don’t grasp or understand what it means [to be prejudiced], and I can’t say that I fully do, especially growing up here where it’s so white dominated, it’s just kind of written into people. There isn’t enough of a black representation to understand why what they’re saying is problematic,” said William Penni, a senior at Barnstable High School.

Penni has lived on Cape his entire life and his family has been here for over two decades.

“I’ve made stupid jokes, said words and made stupid comments,” Penni said.

Even though Penni believes that jokes can be just that – jokes, he still believes that with every joke you tell, you are orienting yourself in a way that makes you seem prejudiced.

“If you’re willing to make a joke about a stereotype, you just kind of unconsciously start to think that way and that’s what leads to the real racism I’ve seen,” said Penni.

Penni’s reason for this being that people typically stay close to others that they relate to.

“It becomes like than echo chamber where no one will be hurt by it,” said Penni, “But eventually you will say something and someone will be hurt by it and then it’s kind of down to, as a person, are you willing to admit you were wrong or are you gonna say ‘oh well they’re being sensitive’,”

In Penni’s experience, prejudice can be so internalized that people just end up saying that others are too sensitive and that they cannot ‘take a joke’.

“I think a lot of people are used to it,” he said, “There are parents making jokes, their friends are making jokes, and they will never interact with anyone in a meaningful manner; that makes them realize that what they are doing is problematic,”

Penni believes that half of the people who make racially insensitive jokes, who say things that could affect people, don’t even see themselves as the issue.

The kinds of people who are willing to make a joke at the expense of others don’t recognize they are hurting anyone because it’s just a part of their lives.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Barnstable High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Brandon Byrd • May 29, 2025 at 7:42 PM

This is incredible.